Seven college boys move into the carriage house at the end of August. I watch from my bay window as they punch the code to the door. They carry in televisions, microwaves, and cases of beer.

My cell phone vibrates. It’s my mother. She wishes me a happy birthday and says my gift is in the mail. I ask about the humidity in Florida and her hip. She says, “How’s the plantation?” It’s a bad joke. She never liked the size of my house, or my dead husband, or the fact that we need landscapers and maids. Had the money been mine, her feelings might have been different. Mom and I used to plot my escape from the confines of our two-bedroom apartment. I was supposed to become a doctor.

I hang up and then call a pizza place. I order seven large pizzas for the boys in the carriage house. I realize that’s probably too much and call the pizza place back. The line’s now busy. So I just wait in the bay window, anxious to see the food arrive, and fiddle with the dating app on my phone.

The app is for widows. I enjoy the messages I receive from the men, mostly. I respond to someone named Jeremy. His interests are skiing, books, and politics. I say that, Yes, I’d like to get a drink sometime. And then I wait on a response.

The food arrives at the carriage house. The boys all come out and lounge in the grass, pizza boxes spread around them. Napkins flutter away in the breeze. They drink cans of beer and arm wrestle. It’s almost dark when two of them cross the expansive lawn and approach my house.

I quickly assess myself in the mirror. Athleisurely unkempt. A small impulse to apply eyeliner makes me laugh, and I don’t.

They are so happy, standing in my doorway, smelling of light beer. They thank me for the pizza and say their names are Curtis and Steve. They promise me tickets to their next game. I don’t have the heart to say that I get free admission because of my husband’s history of donations to the school. (We went once, long ago, and it was fine.) There’s an awkward lull in the conversation. I tell them that a new washer and dryer will be arriving at the carriage house tomorrow. They say I’m the greatest landlady of all time.

I take an Ambien and try to fall asleep in the glow of a muted television. I can’t. Sleep was a casualty of my husband’s passing. I try to use it as evidence of a love between us. We did sacrifice for each other. I dropped out of medical school. He left his first wife. My mother harbors deep suspicions of men with multiple marriages. She likes that my father failed to find another woman to take him in.

About my marriage, my mother often asked, “Why you?” I never had the heart to share my suspicions. I believe my husband enjoyed the stories of my impoverished youth. The markings of my poverty—bad teeth, alcoholic genes, Boston accent—they did something for him. Distinct from the immaculate breeding of his first wife. Strange, I know, but she hurt him, and so I was the follow-up.

I open WidowMingle on my phone and respond to a man named Javier with interests in wine, wonder, and the Great Outdoors. He looks beautiful in a familiar way. Tell me more about your vineyard, I write. I’m curious. He messages right back to say he can tell me all about it: Tomorrow night, Scala’s at seven? I don’t respond.

In the morning, I find that I did respond, confirming these plans with Javier. Embarrassing to not remember, but I’ve sent far more embarrassing Ambien messages before.

A positive memory of my husband: We used to garden together before lunch. This was in the months between his retirement and passing. A habit nearly formed. Now I only have the landscapers for company. They trim the hedges and groom the acres of grass. I garden. The Ambien must be in my system still, because I make the mistake of watering first and weeding second, which leaves me on my hands and knees in dirt that’s turned to mud. I’m filthy in minutes. I slop up and down the rows. The landscapers smile at me, and I tip the wide brim of my hat with a sopping glove.

Glenda, my maid, emerges from the house. She tells me the delivery men abandoned the new washer and dryer at our front door instead of the carriage house. One of the landscapers offers to help me, but I wave him off.

When my husband retired, the gardening was so good for us. He would look at me, incredulous, interested, and say things like, “Who are you?” It was a good question, and one I would have asked him every year prior, but now, given the chance, I didn’t need to. He was the man purchasing trowels and rakes and edgers. He was the man telling the landscapers to leave the garden to us. He bought me a tractor for my birthday.

Seemed like we were just starting something, and then: a heart attack at the dinner table. Horrible in its particularities.

Chair upended.

Marinara sauce smeared on his elbow.

Wine trembling in his glass even as he stopped moving on the floor.

I drive the tractor out from the garage, pull it around the house, and leave it idling by the washer and dryer. I arrange a tarp, and try to tip them onto it. I fail. A landscaper approaches and I tell him, “No, thank you.” Then I put my back to each machine, brace my feet, and push hard. They fall sideways onto the tarp. They don’t sound like they break.

I rope the edges of the tarp to the tractor and put it in gear. I leave a wake of flattened grass.

I’m triumphant as I cross the lawn and near the carriage house. The Ambien has left my system. The boys are out now, erecting a volleyball net, and they wave at me. I hold a muddy fist in the air. They applaud. If my husband could see me now….

“Can we get you a drink?” one of the boys says. I think it is Curtis, from the night before.

“Can we give you a tour?” another boy says. His tone is seductive. The other boys laugh, and my skin flushes. I feel attractive.

“We’re hitting the town tonight,” says the boy who might be Curtis. “Maybe you’ll join us?”

I leave them with the two huge units and drive away, the empty tarp a fluttering cape behind me.

I arrive late at Scala’s that night, and when Javier stands to greet me, I recognize him: one of my landscapers.

We both take out our phones and measure the WidowMingle profile pictures against the person sitting across from us. Javier’s picture matches the man across from me perfectly. Mine, less so. It’s an old picture.

I expect Javier to flee on the grounds of professionalism, but he just turns to the waiter and orders a bottle of wine. I like this. He is a beautiful man.

“Your wife?” I ask. This is how WidowMingle dates usually start.

“Cancer,” he says. “Faster even than the doctors thought it would be.”

“My husband died of a heart attack,” I say.

“I know,” Javier says. And that’s right, I know he knows, because I remember how the landscapers stopped lifting their equipment into their trailer to watch as my husband was lifted into the ambulance.

When the wine arrives, Javier says, “My wife and I, we visited this winery in California on our honeymoon. It is very good.”

The second bottle we order is even better, and we stop talking about the dead, and begin talking about my flowers.

“You have the gift, you know? They spring to life for you. It is so wonderful to see,” Javier says.

“But you,” I say. “With a vineyard. What a waste to have you mowing my lawn.” He shrugs.

“My mother and father tend to the grapes. Keeps them busy. I bring home the money,” he says. I want to ask him if we pay him well, because I have no idea. I don’t, though, and instead try to put my hand on his. I spill wine into my pasta.

Javier seems disappointed when I insist on paying for the meal. His Uber arrives and he is hesitant to leave me. I tell him my Uber is not far behind. He kisses me on the cheek and leaves. I walk a block, find my car, and decide I’ll listen to the radio until I’m sober enough to drive. For some reason, I wish I had told Javier about dropping out of medical school. I want him to know me. I nod off, and when I wake up, it is past midnight. I drive away from downtown with my foot heavy on the pedal.

I nearly hit the boys when I come around a dark curve in the road. I stop just past them and count six approaching in the red glow of my brake lights. There’s not an ounce of suspicion or fear about them as they near my vehicle. Just merry waves and boozy swagger. I lower my window and offer them a ride. Upon recognizing me, they applaud for the second time that day.

Curtis sits on the lap of an even larger boy in the passenger seat, and four more press shoulders in the back. They want to tell me all about their night.

“And the bowling alley was BYOB–”

“So we brought in as much as we could carry–”

“But then they tried to card Tommy when he passed out in the bathroom–”

“So we had to try and finish the beers before they walked him out–”

“But I wasn’t even passed out, it was a diversion–”

“And so that’s how we all got bowling shoes–”

“But I don’t think we can ever go back–”

The boys pile out in front of the carriage house, and Curtis reaches back to offer me his hand, and I take it, and then he plants a sloppy kiss on my knuckles while the other boys hoot.

“Seriously. Thank you,” Curtis says.

“Bedtime, boys,” is all I can think to respond with. They laugh and begin tossing cardboard into the fire pit.

I sit in my bay window and watch them drink dozens more beers around the fire. One of them strums an acoustic guitar and they all limp through Sweet Home Alabama.

I am still a bit drunk, I realize, and also getting itchy from what might be poison ivy on my shins. There’s a set of new gardening tools on the kitchen counter, and I select the forked tines. I use it to scratch through the fabric of my tights, but then I remove them, and it feels even better to draw the tool across my bare skin.

The boys continue singing far outside my window, and tiger stripes of red scratched skin show on my shins, and then my thighs. I sigh and remember trying to conceive. My husband admitted to the vasectomy after we’d been married for five years. I press the handle between my legs and think about Javier and his hands and red wine.

It is still dark when I wake to the sound of my living room window squeaking. It lifts, and then so does the screen, and a leg appears, followed by the rest of a drunk boy.

It is Curtis, and he is very sick from drinking. He cries on my living room floor. He thinks he might be dying. I help him into the bathroom, and he vomits into the toilet intermittently for an hour. I sit on the edge of the tub, and he falls asleep with his head on the toilet seat. His stomach appears to be empty, and I manage to walk him to the living room couch. I cover him with a sheet, and then worry that he might actually be dead, because he’s so pale and still. But the snoring starts, and it’s loud enough for me to hear from my bedroom, where I collapse just as daylight is appearing outside my window. No Ambien needed.

The next morning is strange. It’s late. Curtis is gone, and he left no note of thank you or apology, which disappoints me. There’s a lingering smell of bile in the living room, so I open all of the windows. I apply hydrocortisone to the poison ivy on my shins. Glenda arrives at noon and brings me the mail.

My birthday gift from my mother has arrived. A large padded envelope containing a singing card (It’s Raining Men, Hallelujah) and a book about finding God in widowhood. Ugh. This is a thing now, apparently: My mother found God in Florida.

In addition to the gift, the first fall edition of the college’s student newspaper has arrived.

The front-page spread shows a hulking white house with beautiful flowers, and I admire them for a moment before realizing that they are myflowers and it is my house. Above the image, the headline: College Donor’s House Built By Slaves, and below: Ashby Learning Center’s Namesake, Laurence Ashby, Lived in Slave-Built House. In the article, mention of my husband’s multi-million dollar donations to the school, the subsequent construction of the learning center that bears his name, and archival documents from the college library tracing his lineage to slave owners. Student activists on campus are calling for the learning center to be renamed.

Glenda informs me of the arrival of a mound of mulch. I usually garden in the lingering coolness of morning, but my slow start leaves me in brutal sunlight. The mulch is brown, heavy, and dank, and I spread it in my flower beds. I fight dehydration until my vision begins to waver, and I rise from my flowers to see the protestors standing at the edge of my property.

It’s a small group, and I can’t make out the exact words they’ve positioned in blocky fonts on their signs. I’m glad it’s a Saturday, and that Javier and his crew will not be returning until Monday. If he had seen this, I might have died of embarrassment.

When I drink water in the kitchen, I find a message from Javier on my phone. He says that last night was lovely, and that he will be bringing me a gift on Monday. My pulse increases, and I feel dizzy and light.

On Sunday, I garden with a larger audience of protestors. They are not so quiet this time, and chant about dirty money. Their words lodge in my head, and I repeat them as I work. I manage to spread the last of the mulch in my garden, all the way up to the edge of the house. I water the flowers with the hose. A rainbow hangs in the mist before me. Curtis and two other boys approach me.

“We can take care of them, you know,” Curtis says.

“I don’t know who they think they’re yelling at,” one of the others says.

I manage to get rid of the boys, telling them to enjoy their weekend, to do their homework. I rather like them. I figure things will die down on Monday when the students are in class and the adults are at work.

But things do not die down. My poison ivy is also spreading, and my Ambien may have reacted weirdly with some steroids I took to fight the rash, because I sleep hard until noon, and wake to find a massive crowd lining my property.

The boys must be skipping class, because I can see them through the bay window, talking to reporters. I wonder if they’ve turned on me. But no, they haven’t, because they are red-faced, and standing shoulder-to-shoulder against the sea of protestors.

I decide I’ll garden anyways, because what else can I do? I try, but it is incredibly hot. So much so that patches of mulch are smoking. I suppose I’m trying to distract myself from Javier, who is on my property and trimming the hedges.

He approaches me. I offer him a glass of water up in the kitchen. We both tromp dirt through the foyer, and this feels like the right thing to do. He doesn’t mention the protestors, but instead proffers a bottle of wine.

“From my vineyard,” he explains. I hold the bottle in my hands, and then I move to kiss him on the cheek, but he leans in and kisses me on the lips. He is salty with sweat and so am I.

I pull away and reach for something, anything, to say. “I think I’ll just talk to the reporters,” I let out. Javier shrugs.

“I always thought your husband was a good man,” he says. It’s my turn to shrug. We tromp more mud through the house, exit, and approach the crowd.

Microphones in our faces. Cameras trained.

“Will you continue to work for the family in light of recent events?” Directed at Javier, but also at me. I’m proud to be mistaken for a landscaper.

“Is the wife home? Will she comment?” Again, directed at both of us.

“She is home, but says she will not comment,” I say.

A reporter: “Is there a chance you will go on strike?”

“We are figuring that out now,” I say.

“She is a widow,” Javier says, not looking at me. “The blood is not on her hands.”

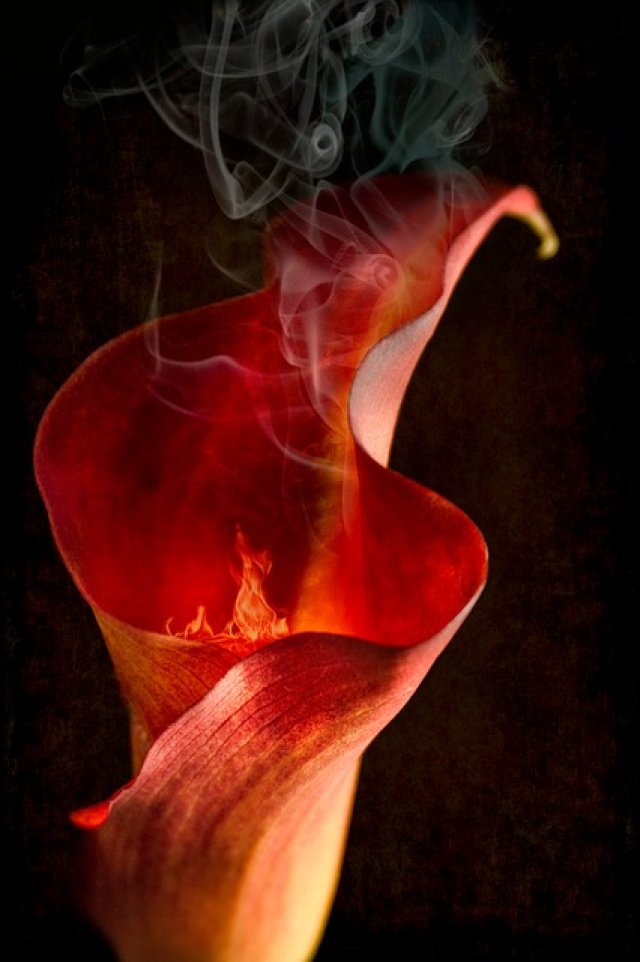

“But, if that’s true, why won’t she come out?” This is shouted by a protester, but not at us, at the house, so we turn to face it. The flowers, the house, waver mirage-like in the heat. But it’s not just the heat, there’s also the smoking mulch. The crowd chants. The heat increases. Then there is cheering, because a flame shows among the flowers, rising through the smoke. The mulch is on fire.

It’s a ludicrous vision to behold: the bright white of my husband’s hulking house, embroidered by flowers and flames.

I hold Javier’s hand to prevent him from phoning the fire department. The crowd continues to chant, and maybe I join them. The house might be catching now. I imagine a widow, deep in Ambien slumber, whose dreams race to explain why her body is turning to ash.